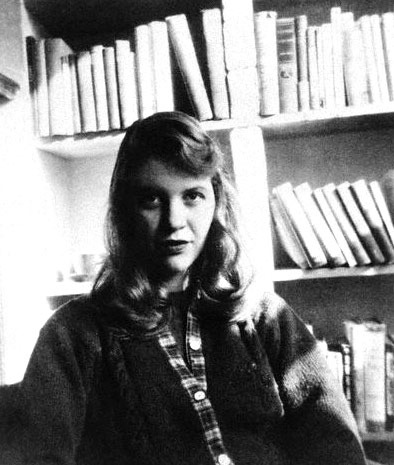

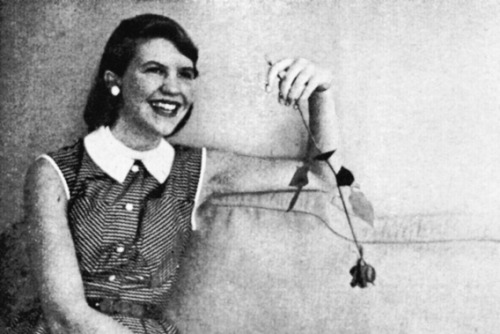

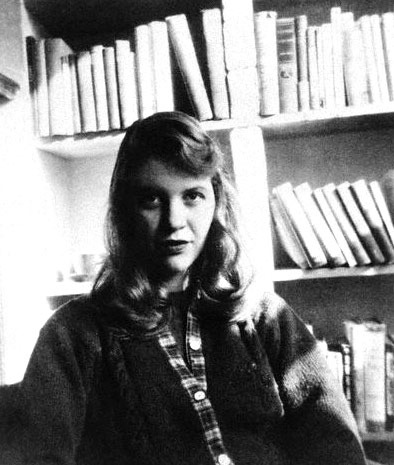

Sylvia Plath (27 oktober 1932 – 11 februari 1963) was een Amerikaanse dichteres, romanschrijfster en essayiste. Hoewel ze vooral bekend is om haar poëzie, oogstte ze ook faam met haar semi-autobiografische roman The Bell Jar ("De glazen stolp"), waarin haar worsteling met depressies gedetailleerd wordt beschreven. Na haar zelfmoord is ze voor velen een icoon geworden.

![Picture via Peter K. Steinberg’s blog post from 27 October 2012 “Gail Crowther visits Heptonstall on Sylvia Plath’s Birthday”***The “Sylvia Plath Calendar” - 52 years ago today:According to her death certificate, Sylvia Plath’s funeral took place on Monday 18 February 1963 in Heptonstall’s parish churchyard of St Thomas the Apostle, the new St Thomas á Beckett’s churchyard; near Ted Hughes’ birthplace Mytholmroyd in West Yorkshire, England.Her epitapth reads: “Even amidst fierce flames the golden lotus can be planted.” (More on that here).In her memoir Giving Up: The Last Days of Sylvia Plath (which I am not the biggest fan of, but it still contains a few interesting facts), Jillian Becker, Sylvia Plath’s friend, whom Plath spend her last days with, devotes a whole chapter to Sylvia Plath’s funeral. I compiled the most interesting passages for you:“Sylvia had pictured her grave in undulating Devon, not fliny Yorkshire where she lies. Soon after we met she told me, speaking of her death as a far-off event, that she’d like to be buried in the churchyard next to Court Green. Had she never said as much to Hughes? I suppose if he’d held the funeral down there, none of his family would have come to it.” (p. 25)“The service in the church was short. For a few moments sunlight came through a stained-glass window, enriching the yellow in it. We followed her coffin to the grave, a yellow trench in the snow, it’s banked up mud the same colour as the stained-glass, but thick as oil-paint freshly poured out. Beside it the rite was completed. ‘I’ll stay here alone for a while,’ Hughes said.[…]He rejoined the funeral guests soon after we were seated, fourteen or so in all, round a table in a private upper room of a pub in the village.[…]Only four of us were there 'for Sylvia’: Warren [Sylvia Plath’s brother] and Margaret, Gerry and I. The rest were there 'for Ted’ […].[…]When the tea had been poured and steak-and-kidney pies sat down at each place, Hughes blurted out vehemently but quietly, as if only for Gerry and me to hear though he looked at neither of us: 'Everybody hated her.’ […]'It was either her or me,’ he said […].” (p. 26)“A moment came when he seemed to feel a need to vindicate himself to Gerry and me. He said: 'I told her everything was going to be all right. I said that by summer we’d all be back together at Court Green.’ ” (p. 27)“In another burst of speech he asked me it I’d read The Bell Jar. I told him I had. And did I know that it was autobiographical? I did. So I also knew that she’d tried to kill herself before they’d met? I did. 'It was in her, you see,’ he said. 'But I told her that if she wrote about it profoundly enough, she would conquer it.’'And you don’t think she wrote about it profoundly enough?’'No.’ His 'no’ was a sort of verbal shrug, implying: 'obviously not - doesn’t this funeral prove it?’ ” (p. 28)](http://40.media.tumblr.com/832ba5a199bea10c58ab6e582220b41e/tumblr_njvm1bsP9u1qadfqfo1_500.jpg)

![via (http://blogs.ancestry.com)Cause of death: “[…] Carbon Monoxide Poisoning (domestic gas) whilst suffering from

depression. Did kill herself.”](http://36.media.tumblr.com/tumblr_kvy21dXxNi1qadfqfo1_500.jpg)

Sylvia Plath werd geboren in Jamaica Plain, een buitenwijk van Boston. Haar talent uitte zich al vroeg, ze schreef haar eerste gedicht toen ze acht jaar oud was. Haar vader Otto Plath, hoogleraar zoölogie en Duits, en auteur van een boekje over hommels, overleed rond die tijd, op 5 oktober 1940. Plath zette haar literaire aspiraties door, probeerde gedichten en verhalen in Amerikaanse tijdschriften gepubliceerd te krijgen en oogstte enig succes.

Sylvia leed gedurende haar gehele volwassen leven aan een ernstige vorm van depressie, een bipolaire stoornis. In 1950 werd ze met een beurs toegelaten tot Smith College, maar al in haar eerste studiejaar deed ze een zelfmoordpoging. Ze kwam onder behandeling van een psychiatrische instelling (McLean Hospital) en leek goed te herstellen. In 1955 studeerde ze cum laude af.

Plath kreeg opnieuw een beurs, ditmaal om aan de universiteit van Cambridge te gaan studeren. Ook daar schreef ze gedichten, die af en toe in de studentenkrant Varsitywerden gepubliceerd. In Cambridge ontmoette ze de Engelse dichter Ted Hughes, met wie ze trouwde op 16 juni 1956. Plath en Hughes woonden van juli 1957 tot oktober 1959 in de Verenigde Staten, waar Plath les gaf aan Smith College. In Boston woonde Plath lezingen van Robert Lowell bij, die van grote invloed op haar werk zouden zijn. In deze tijd ontmoetten Plath en Hughes ook William Merwin, die hun werk bewonderde en een vriend voor het leven zou worden. Toen Sylvia zwanger was verhuisde het echtpaar terug naar het Verenigd Koninkrijk.

Ze woonden een tijdje in Londen en streken vervolgens neer in North Tawton, een stadje in Devon. Haar eerste dichtbundel, The Colossus, kwam in 1960 in Engeland uit. In februari 1961 kreeg ze een miskraam, waarnaar ze in een aantal gedichten verwees. Door echtelijke ruzie, vooral naar aanleiding van Hughes' affaire met dichteres Assia Wevill, leefden Ted en Sylvia na de geboorte van hun eerste kind bijna twee jaar gescheiden.

Plath keerde met haar kinderen Frieda en Nicholas terug naar Londen. Ze huurde een woning in een appartementencomplex waar ook William Butler Yeats ooit woonde. Plath was hier erg blij mee en beschouwde het als een goed voorteken toen ze haar scheidingsprocedure inzette. De winter van 1962/1963 was zeer streng en Sylvia werd ziek. Op 11 februari 1963 verstikte ze zichzelf met het gas van haar oven. Voordien had ze nog eten en melk voor haar kinderen klaargezet. Ze ligt begraven op het kerkhof van Heptonstallin West Yorkshire.

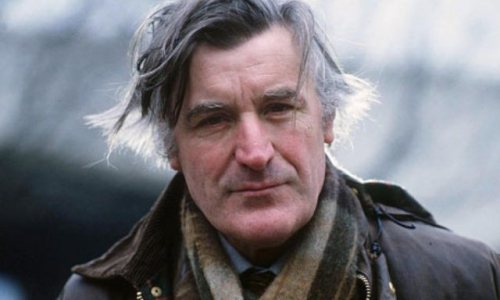

Ted Hughes kreeg het beheer over Plaths persoonlijke en literaire nalatenschap. Hij vernietigde het laatste deel van Sylvia's dagboek, waarin hun tijd samen beschreven werd. In 1982 werd Plath de eerste dichter die postuum een Pulitzer-prijs won (voor The Collected Poems).

Veel critici, vooral uit feministische hoek, hebben Hughes ervan beschuldigd bij de publicatie van Plaths werken vooral zijn persoonlijke doeleinden na te streven. Hughes heeft dit altijd ontkend. In zijn laatste dichtbundel, Birthday Letters, doorbrak hij uiteindelijk zijn stilzwijgen rond Sylvia.

Een vergelijkbaar verwijt trof overigens Sylvia's moeder, Aurelia Schober Plath, toen zij een selectie van Sylvia's brieven aan haar, Letters Home by Sylvia Plath. Correspondence 1950 — 1963, uitgaf (1975). Aurelia zou een keuze hebben gemaakt die vooral haarzelf in een gunstig daglicht stelde.

Hoewel Plaths eerste boek, The Colossus, over het algemeen goed ontvangen werd door de critici, wordt ook wel gezegd dat het nogal conventioneel is en het drama mist dat in haar latere werk zo sterk tot uitdrukking komt. Hoeveel invloed Hughes op Plaths werk heeft gehad is onderwerp van discussie. Plaths gedichten hebben een geheel eigen stem en de overeenkomsten tussen het werk van beide dichters zijn niet erg groot.

De gedichten in de bundel Ariel markeren een breuk met Plaths eerdere werk. Waarschijnlijk hebben de lessen van Lowell daarbij een rol gespeeld. Hoe het ook zij, de bundel heeft een zeer dramatische uitwerking, vooral door de uiterst oprechte en intieme beschrijvingen van Sylvia's psychische gesteldheid en de autobiografische gedichten (o.a.Daddy waarin ze haar vader om zijn vroege dood als verrader afschildert). Plaths werk wordt vaak in verband gebracht met dat van Anne Sexton, die net als Sylvia sterk beïnvloed werd door Robert Lowell. Ondanks de vele kritieken en biografieën die na haar dood zijn verschenen lijkt de discussie over Plaths werk vaak op een gevecht tussen lezers die Sylvia's kant kiezen en lezers die achter Hughes staan. De bitterheid die sommige mensen jegens Hughes koesteren is af te lezen aan vele pogingen om Hughes' naam van Sylvia's grafsteen te verwijderen.

Poëzie

- The Colossus (1960)

- Ariel (1965)

- Crossing the Water (1971)

- Winter Trees (1972)

- The Collected Poems (1981)

Proza

- The Bell Jar (De glazen stolp) (1963), onder het pseudoniem 'Victoria Lucas'

- Letters Home (1975), geschreven aan en samengesteld door haar moeder

- Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams (1977)

- The Journals of Sylvia Plath (1982)

- The Magic Mirror (1989), Plaths eindscriptie aan Smith College

- The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath (2000), samengesteld door Karen V. Kukil

Kinderboeken

- The Bed Book (1976)

- The It-Doesn't-Matter-Suit (1996)

- Collected Children's Stories (2001)

- Mrs. Cherry's Kitchen (2001)

Daddy

You do not do, you do not do Any more, black shoe In which I have lived like a foot For thirty years, poor and white, Barely daring to breathe or Achoo. Daddy, I have had to kill you. You died before I had time-- Marble-heavy, a bag full of God, Ghastly statue with one gray toe Big as a Frisco seal And a head in the freakish Atlantic Where it pours bean green over blue In the waters off beautiful Nauset. I used to pray to recover you. Ach, du. In the German tongue, in the Polish town Scraped flat by the roller Of wars, wars, wars. But the name of the town is common. My Polack friend Says there are a dozen or two. So I never could tell where you Put your foot, your root, I never could talk to you. The tongue stuck in my jaw. It stuck in a barb wire snare. Ich, ich, ich, ich, I could hardly speak. I thought every German was you. And the language obscene An engine, an engine Chuffing me off like a Jew. A Jew to Dachau, Auschwitz, Belsen. I began to talk like a Jew. I think I may well be a Jew. The snows of the Tyrol, the clear beer of Vienna Are not very pure or true. With my gipsy ancestress and my weird luck And my Taroc pack and my Taroc pack I may be a bit of a Jew. I have always been scared of you, With your Luftwaffe, your gobbledygoo. And your neat mustache And your Aryan eye, bright blue. Panzer-man, panzer-man, O You-- Not God but a swastika So black no sky could squeak through. Every woman adores a Fascist, The boot in the face, the brute Brute heart of a brute like you. You stand at the blackboard, daddy, In the picture I have of you, A cleft in your chin instead of your foot But no less a devil for that, no not Any less the black man who Bit my pretty red heart in two. I was ten when they buried you. At twenty I tried to die And get back, back, back to you. I thought even the bones would do. But they pulled me out of the sack, And they stuck me together with glue. And then I knew what to do. I made a model of you, A man in black with a Meinkampf look And a love of the rack and the screw. And I said I do, I do. So daddy, I’m finally through. The black telephone’s off at the root, The voices just can’t worm through. If I’ve killed one man, I’ve killed two-- The vampire who said he was you And drank my blood for a year, Seven years, if you want to know. Daddy, you can lie back now. There’s a stake in your fat black heart And the villagers never liked you. They are dancing and stamping on you. They always knew it was you. Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through.

12 October 1962

Lady Lazarus

I have done it again. One year in every ten I manage it-- A sort of walking miracle, my skin Bright as a Nazi lampshade, My right foot A paperweight, My face a featureless, fine Jew linen. Peel off the napkin O my enemy. Do I terrify?-- The nose, the eye pits, the full set of teeth? The sour breath Will vanish in a day. Soon, soon the flesh The grave cave ate will be At home on me And I a smiling woman. I am only thirty. And like the cat I have nine times to die. This is Number Three. What a trash To annihilate each decade. What a million filaments. The peanut-crunching crowd Shoves in to see Them unwrap me hand and foot-- The big strip tease. Gentlemen, ladies These are my hands My knees. I may be skin and bone, Nevertheless, I am the same, identical woman. The first time it happened I was ten. It was an accident. The second time I meant To last it out and not come back at all. I rocked shut As a seashell. They had to call and call And pick the worms off me like sticky pearls. Dying Is an art, like everything else. I do it exceptionally well. I do it so it feels like hell. I do it so it feels real. I guess you could say I’ve a call. It’s easy enough to do it in a cell. It’s easy enough to do it and stay put. It’s the theatrical Comeback in broad day To the same place, the same face, the same brute Amused shout: ‘A miracle!' That knocks me out. There is a charge For the eyeing of my scars, there is a charge For the hearing of my heart-- It really goes. And there is a charge, a very large charge For a word or a touch Or a bit of blood Or a piece of my hair or my clothes. So, so, Herr Doktor. So, Herr Enemy. I am your opus, I am your valuable, The pure gold baby That melts to a shriek. I turn and burn. Do not think I underestimate your great concern. Ash, ash-- You poke and stir. Flesh, bone, there is nothing there-- A cake of soap, A wedding ring, A gold filling. Herr God, Herr Lucifer Beware Beware. Out of the ash I rise with my red hair And I eat men like air.

23-29 October 1962

Morning Song

Love set you going like a fat gold watch. The midwife slapped your footsoles, and your bald cry Took its place among the elements. Our voices echo, magnifying your arrival. New statue. In a drafty museum, your nakedness Shadows our safety. We stand round blankly as walls. I’m no more your mother Than the cloud that distills a mirror to reflect its own slow Effacement at the wind’s hand. All night your moth-breath Flickers among the flat pink roses. I wake to listen: A far sea moves in my ear. One cry, and I stumble from bed, cow-heavy and floral In my Victorian nightgown. Your mouth opens clean as a cat’s. The window square Whitens and swallows its dull stars. And now you try Your handful of notes; The clear vowels rise like balloons.

Got some Sunday goodies for you… in honor of Mother’s Day I give you Sylvia Plath with her children Frieda and Nicholas in 1962 at Court Green, Devon in 1962.

In 1986, 23 years after the death of Sylvia Plath, 56-year-old Ted Hugheswrote the following letter to their 24-year-old son Nicholas Hughes:

![Picture via Peter K. Steinberg’s blog post from 27 October 2012 “Gail Crowther visits Heptonstall on Sylvia Plath’s Birthday”***The “Sylvia Plath Calendar” - 52 years ago today:According to her death certificate, Sylvia Plath’s funeral took place on Monday 18 February 1963 in Heptonstall’s parish churchyard of St Thomas the Apostle, the new St Thomas á Beckett’s churchyard; near Ted Hughes’ birthplace Mytholmroyd in West Yorkshire, England.Her epitapth reads: “Even amidst fierce flames the golden lotus can be planted.” (More on that here).In her memoir Giving Up: The Last Days of Sylvia Plath (which I am not the biggest fan of, but it still contains a few interesting facts), Jillian Becker, Sylvia Plath’s friend, whom Plath spend her last days with, devotes a whole chapter to Sylvia Plath’s funeral. I compiled the most interesting passages for you:“Sylvia had pictured her grave in undulating Devon, not fliny Yorkshire where she lies. Soon after we met she told me, speaking of her death as a far-off event, that she’d like to be buried in the churchyard next to Court Green. Had she never said as much to Hughes? I suppose if he’d held the funeral down there, none of his family would have come to it.” (p. 25)“The service in the church was short. For a few moments sunlight came through a stained-glass window, enriching the yellow in it. We followed her coffin to the grave, a yellow trench in the snow, it’s banked up mud the same colour as the stained-glass, but thick as oil-paint freshly poured out. Beside it the rite was completed. ‘I’ll stay here alone for a while,’ Hughes said.[…]He rejoined the funeral guests soon after we were seated, fourteen or so in all, round a table in a private upper room of a pub in the village.[…]Only four of us were there 'for Sylvia’: Warren [Sylvia Plath’s brother] and Margaret, Gerry and I. The rest were there 'for Ted’ […].[…]When the tea had been poured and steak-and-kidney pies sat down at each place, Hughes blurted out vehemently but quietly, as if only for Gerry and me to hear though he looked at neither of us: 'Everybody hated her.’ […]'It was either her or me,’ he said […].” (p. 26)“A moment came when he seemed to feel a need to vindicate himself to Gerry and me. He said: 'I told her everything was going to be all right. I said that by summer we’d all be back together at Court Green.’ ” (p. 27)“In another burst of speech he asked me it I’d read The Bell Jar. I told him I had. And did I know that it was autobiographical? I did. So I also knew that she’d tried to kill herself before they’d met? I did. 'It was in her, you see,’ he said. 'But I told her that if she wrote about it profoundly enough, she would conquer it.’'And you don’t think she wrote about it profoundly enough?’'No.’ His 'no’ was a sort of verbal shrug, implying: 'obviously not - doesn’t this funeral prove it?’ ” (p. 28)](http://40.media.tumblr.com/832ba5a199bea10c58ab6e582220b41e/tumblr_njvm1bsP9u1qadfqfo1_500.jpg)

Sylvia Plath’s grave in Heptonstall in late 1988. When a third tombstone was removed from Plath’s grave because, as had happened with the previous two stones, vandals chiseled off the name “Hughes” from “Sylvia Plath Hughes,” a local resident erected a handmade cross that bore only “Sylvia Plath”.

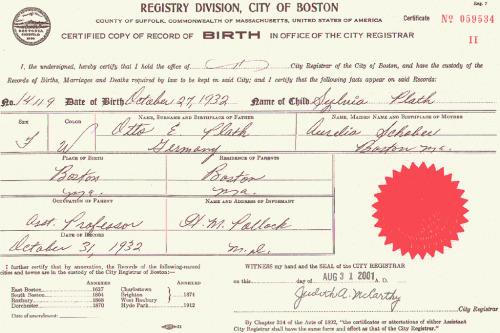

![via (http://blogs.ancestry.com)Cause of death: “[…] Carbon Monoxide Poisoning (domestic gas) whilst suffering from

depression. Did kill herself.”](http://36.media.tumblr.com/tumblr_kvy21dXxNi1qadfqfo1_500.jpg)

Cause of death: “[…] Carbon Monoxide Poisoning (domestic gas) whilst suffering from depression. Did kill herself.”

Sylvia Plath’s and Ted Hughes’ second child, Nicholas Farrar Hughes, was born on Wednesday, 17 January 1962 at Court Green in North Tawton, Devon, England, after more than eighteen hours of labor.

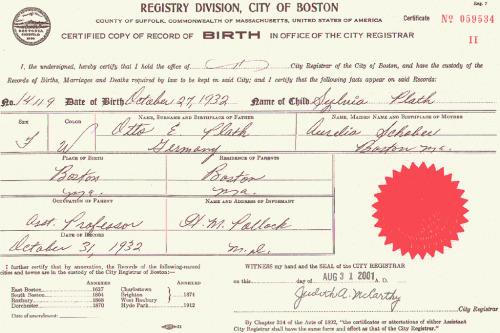

Sylvia Plath’s birth certificate

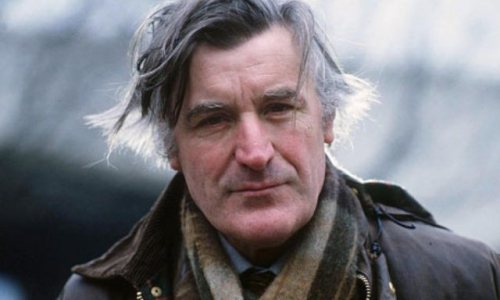

Ted Hughes, born 17 August 1930, died 28 October 1998

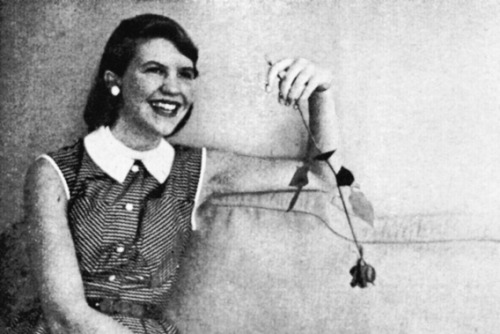

Sylvia, almost seventeen, with her brother Warren and her mother Aurelia in September 1949”

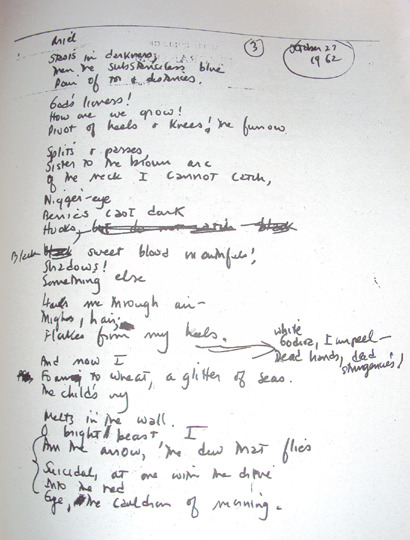

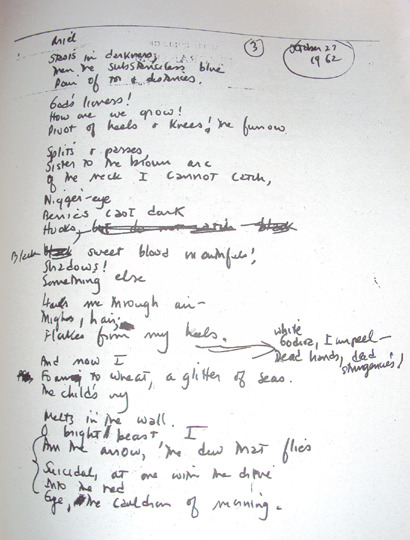

“ ‘Ariel’ - A facsimile of the last lines written in Ms Plath’s own hand”

Otto Plath!

(April 13, 1885 – November 5, 1940)

Picture: Otto Plath, 1930

Frieda Hughes in 1962 at the age of almost two

“Frieda Hughes unveils a blue plaque in memory of her mother, Sylvia Plath, in Chalcot Square, Primrose Hill, London in 2000. Picture: Nigel Sutton”

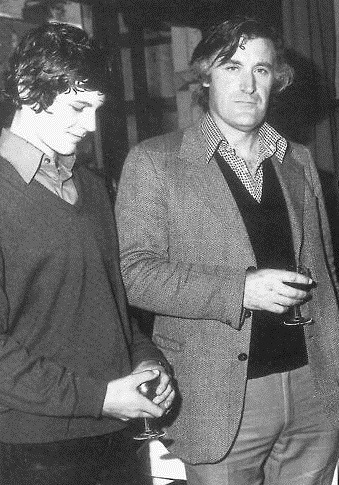

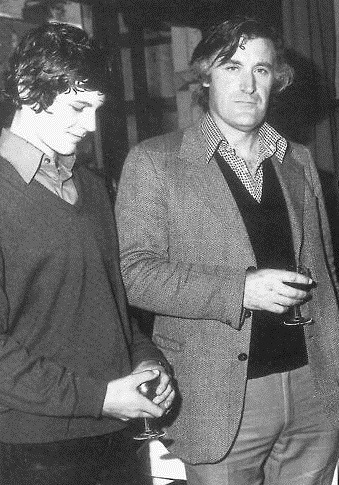

Strong relationship: Nicholas with his father, Ted Hughes, and sister Freid

Nicholas, right, with his father's widow Carol and sister Freida, left, at a memorial service for Ted Hughes at Westminster

Nicholas, right, with his father's widow Carol and sister Freida, left, at a memorial service for Ted Hughes at Westminster Abbey in 1999

Nicholas Hughes moved to Alaska for the fishing, not to escape his demons

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten