Virginia Woolf (Londen, 25 januari 1882 – Lewes (Sussex), 28 maart 1941) was een Brits schrijfster en feministe. Tussen de Eersteen de Tweede Wereldoorlog was Woolf een belangrijke figuur in het literaire leven van Londen. Ze was lid van de Bloomsburygroep.

Gerald Duckworth, Virginia Woolf, Thoby Stephen, Vanessa Stephen, and George Duckworth (back row); Adrian Stephen, Julia Duckworth Stephen, and Leslie Stephen (front row) at Alenhoe, Wimbledon in 1892

Vanessa Bell, Julia Jackson Stephen, Thoby Stephen, Adrian Stephen, and Virginia Woolf in 1894

Adrian, Thoby, Vanessa and Virginia, 1892

1892 - from left to right. Horatio Brown, Julia Duckworth Stephen, George Duckworth, Gerald Duckworth, Vanessa, Thoby, Virginia, Adrian Stephen, the dog Shag

A young Vanessa Bell paints while her sister, Virginia Woolf, and two brothers, Thoby and Adrian, look on

The Stephen children; Adrian, Thoby, Vanessa and Virginia

Thoby, Vanessa, Virginia, Julia, and Adrian Stephen, 1894. Plate 38a Leslie Stephen Photograph Album, Smith College.

(back row) Virginia (Woolf), Vanessa (Bell), Thoby Leslie Stephen ; (front row) Gerald Duckworth, Adrian Stephen Stella Duckworth after the death of her mother Julia (Jackson) Stephen - 1895

Julia Jackson Stephen, Vanessa Bell, Thoby Stephen and Virginia Woolf at Talland House in St. Ives in 1894

Angelica Garnett, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, Virginia Woolf, John Maynard Keynes and Lydia Lopokova sitting outside. Picture from Virginia Woolf Monk's House photograph album,

T. S. Eliot and Virginia Woolf

Henry H. H. Cameron (1852-1911): Julia Stephen with Virginia on her lap 1884

In this house LEONARD and VIRGINIA WOOLF lived 1915-1924 and founded the Hogarth Press 1917

Lytton Strachey and Virginia Woolf.

left to right: Noel Olivier; Maitland Radford; Virginia Woolf (née Stephen); Rupert Brooke

Talland House at St. Ives, Cornwall, England. Holiday home of the Stephen family.

Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell plaing cricket

Virginia Woolf sitting in an armchair at Monk's House.

Signature of Virginia Woolf

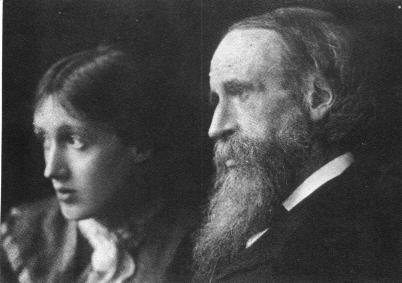

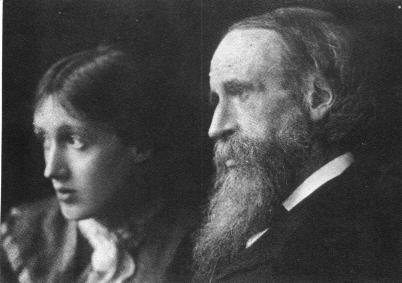

Virginia Woolf with her father, Sir Leslie Stephen (1832-1904)

Virginia Woolf's bed at Monk's House

![Woolf, Virginia [Credit: George C. Beresford—Hulton Archive/Getty Images]](https://lh3.googleusercontent.com/blogger_img_proxy/AEn0k_uszSw3jLJwJHeCBIajxQobSk_mj63KKCfqKKaY8W7QUSBlH8R4IQn-EZ-_oQQN873I2pG7gjmYMA6MKuyeYgY_EXc1qMWz-6W1JTAX8WcdeTibfMKMYv2Nt7LOCYVLuTqD1261fkA=s0-d) The Stephen family made summer migrations from their London town house near Kensington Gardens to the rather disheveled Talland House on the rugged Cornwall coast. That annual relocation structured Virginia’s childhood world in terms of opposites: city and country, winter and summer, repression and freedom, fragmentation and wholeness. Her neatly divided,PREDICTABLE

The Stephen family made summer migrations from their London town house near Kensington Gardens to the rather disheveled Talland House on the rugged Cornwall coast. That annual relocation structured Virginia’s childhood world in terms of opposites: city and country, winter and summer, repression and freedom, fragmentation and wholeness. Her neatly divided,PREDICTABLE world ended, however, when her mother died in 1895 at age 49. Virginia, at 13, ceased writing amusing accounts of family news. Almost a year passed before she wrote a cheerful letter to her brother Thoby. She was just emerging from depression when, in 1897, her half sister Stella Duckworth died at age 28, an event Virginia noted in her diary as “impossible to write of.” Then in 1904, after her father died, Virginia had a nervous breakdown.

world ended, however, when her mother died in 1895 at age 49. Virginia, at 13, ceased writing amusing accounts of family news. Almost a year passed before she wrote a cheerful letter to her brother Thoby. She was just emerging from depression when, in 1897, her half sister Stella Duckworth died at age 28, an event Virginia noted in her diary as “impossible to write of.” Then in 1904, after her father died, Virginia had a nervous breakdown.

![Bell, Vanessa: dust jacket for “To The Lighthouse” [Credit: Between the Covers Rare Books, Merchantville, NJ]](https://lh3.googleusercontent.com/blogger_img_proxy/AEn0k_vqvPJcOAAA1xdVDJj5kAPsfVNjsD6RBj-UAgZNaXdzKoErsfvAez3Fbg6I09-jj4E6uXWijkvDJ1HOUKq49TypxuGpcUdhZjKZOU1nDM-9oi9TdScQTELOKyVqv5YC8VgNo-rcPkBT=s0-d) Woolf wished to build on her achievement in Mrs. Dalloway by merging the novelistic and elegiac forms. As an elegy, To the Lighthouse—published on May 5, 1927, the 32nd anniversary of Julia Stephen’s death—evoked childhood summers at Talland House. As a novel, it broke narrative continuity into a tripartite structure. The first section, “The Window,” begins as Mrs. Ramsay and James, her youngest son—like Julia and Adrian Stephen—sit in the French window of the Ramsays’ summer home while a houseguest named Lily Briscoe paints them and James begs to go to a nearby lighthouse. Mr. Ramsay, like Leslie Stephen, sees poetry as didacticism, conversation as winning points, and life as a tally of accomplishments. He uses logic to deflate hopes for a trip to the lighthouse, but he needs sympathy from his wife. She is more attuned to emotions than reason. In the climactic dinner-party scene, she inspires such harmony and composure that the moment “partook, she felt,…of eternity.” The novel’s middle “Time Passes” section focuses on the empty house during a 10-year hiatus and the last-minute housecleaning for the returning Ramsays. Woolf describes the progress of weeds, mold, dust, and gusts of wind, but she merely announces such major events as the deaths of Mrs. Ramsay and a son and daughter. In the novel’s third section, “The Lighthouse,” Woolf brings Mr. Ramsay, his youngest children (James and Cam), Lily Briscoe, and others from “The Window” back to the house. As Mr. Ramsay and the now-teenage children reach the lighthouse and achieve a moment of reconciliation, Lily completes her painting. To the Lighthousemelds into its structure questions about creativity and the nature and function of art. Lily argues effectively for nonrepresentational but emotive art, and her painting (in which mother and child are reduced to two shapes with a line between them) echoes the abstract structure of Woolf’s profoundly elegiac novel.

Woolf wished to build on her achievement in Mrs. Dalloway by merging the novelistic and elegiac forms. As an elegy, To the Lighthouse—published on May 5, 1927, the 32nd anniversary of Julia Stephen’s death—evoked childhood summers at Talland House. As a novel, it broke narrative continuity into a tripartite structure. The first section, “The Window,” begins as Mrs. Ramsay and James, her youngest son—like Julia and Adrian Stephen—sit in the French window of the Ramsays’ summer home while a houseguest named Lily Briscoe paints them and James begs to go to a nearby lighthouse. Mr. Ramsay, like Leslie Stephen, sees poetry as didacticism, conversation as winning points, and life as a tally of accomplishments. He uses logic to deflate hopes for a trip to the lighthouse, but he needs sympathy from his wife. She is more attuned to emotions than reason. In the climactic dinner-party scene, she inspires such harmony and composure that the moment “partook, she felt,…of eternity.” The novel’s middle “Time Passes” section focuses on the empty house during a 10-year hiatus and the last-minute housecleaning for the returning Ramsays. Woolf describes the progress of weeds, mold, dust, and gusts of wind, but she merely announces such major events as the deaths of Mrs. Ramsay and a son and daughter. In the novel’s third section, “The Lighthouse,” Woolf brings Mr. Ramsay, his youngest children (James and Cam), Lily Briscoe, and others from “The Window” back to the house. As Mr. Ramsay and the now-teenage children reach the lighthouse and achieve a moment of reconciliation, Lily completes her painting. To the Lighthousemelds into its structure questions about creativity and the nature and function of art. Lily argues effectively for nonrepresentational but emotive art, and her painting (in which mother and child are reduced to two shapes with a line between them) echoes the abstract structure of Woolf’s profoundly elegiac novel.

![Woolf, Virginia: dust jacket for “The Waves” [Credit: Between the Covers Rare Books, Merchantville, NJ]](https://lh3.googleusercontent.com/blogger_img_proxy/AEn0k_saVOaUE9ReHlffC0tYFBnqNDcucW0JCYq5LEULQYZgK5zZ4_d2dYf9YzEABO4liJJS5QP8gvPJrRwnCOcN685z_LgUdc0NhfKnL7a1YkSzSP0QxdxsuqC_wd7m9rs_Pwr9LHOdEbGh=s0-d) Having praised a 1930 exhibit of Vanessa Bell’s paintings for their wordlessness, Woolf planned a mystical novel that would be similarly impersonal and abstract. In The Waves (1931), poetic interludes describe the sea and sky from dawn to dusk. Between the interludes, the voices of six named characters appear in sections that move from their childhood to old age. In the middle section, when the six friends meet at a farewell dinner for another friend leaving for India, the single flower at the centre of the dinner table becomes a “seven-sided flower…a whole flower to which every eye brings its own contribution.” The Waves offers a six-sided shape that illustrates how each individual experiences events—including their friend’s death—uniquely. Bernard, the writer in the group, narrates the final section, defying death and a world “without a self.” Unique though they are (and their prototypes can be identified in the Bloomsbury group), the characters become one, just as the sea and sky become indistinguishable in the interludes. This oneness with all creation was the primal experience Woolf had felt as a child in Cornwall. In this her most experimental novel, she achieved its poetic equivalent. Through To the Lighthouse and The Waves, Woolf became, with James Joyce and William Faulkner, one of the three major English-language Modernist experimenters in stream-of-consciousness writing.

Having praised a 1930 exhibit of Vanessa Bell’s paintings for their wordlessness, Woolf planned a mystical novel that would be similarly impersonal and abstract. In The Waves (1931), poetic interludes describe the sea and sky from dawn to dusk. Between the interludes, the voices of six named characters appear in sections that move from their childhood to old age. In the middle section, when the six friends meet at a farewell dinner for another friend leaving for India, the single flower at the centre of the dinner table becomes a “seven-sided flower…a whole flower to which every eye brings its own contribution.” The Waves offers a six-sided shape that illustrates how each individual experiences events—including their friend’s death—uniquely. Bernard, the writer in the group, narrates the final section, defying death and a world “without a self.” Unique though they are (and their prototypes can be identified in the Bloomsbury group), the characters become one, just as the sea and sky become indistinguishable in the interludes. This oneness with all creation was the primal experience Woolf had felt as a child in Cornwall. In this her most experimental novel, she achieved its poetic equivalent. Through To the Lighthouse and The Waves, Woolf became, with James Joyce and William Faulkner, one of the three major English-language Modernist experimenters in stream-of-consciousness writing.

![Woolf, Virginia [Credit: Gisèle Freund]](https://lh3.googleusercontent.com/blogger_img_proxy/AEn0k_tMieYw3RpO5SpGBHPEo9avHpeso-zJ7GUF3fwdz1H_UwQGM245aJAli1zQ3t_JQdJUqvmvdJ7rKWWkxe9gATd6uFXranqAXmj7bg6v_8JdgvRgIFuvWcNUNVp28MRyY4JmwB-PSgl9=s0-d) Woolf’s experiments with point of view confirm that, as Bernard thinks inThe Waves, “we are not single.” Being neither single nor fixed, perception in her novels is fluid, as is the world she presents. While Joyce and Faulkner separate one character’s interior monologues from another’s, Woolf’s narratives move between inner and outer and between characters without clear demarcations. Furthermore, she avoids the self-absorption of many of her contemporaries and implies a brutal society without the explicit details some of her contemporaries felt obligatory. Her nonlinear forms invite reading not for neat solutions but for an aesthetic resolution of “shivering fragments,” as she wrote in 1908. While Woolf’s fragmented style is distinctly Modernist, her indeterminacy anticipates a postmodern awareness of the evanescence of boundaries and categories.

Woolf’s experiments with point of view confirm that, as Bernard thinks inThe Waves, “we are not single.” Being neither single nor fixed, perception in her novels is fluid, as is the world she presents. While Joyce and Faulkner separate one character’s interior monologues from another’s, Woolf’s narratives move between inner and outer and between characters without clear demarcations. Furthermore, she avoids the self-absorption of many of her contemporaries and implies a brutal society without the explicit details some of her contemporaries felt obligatory. Her nonlinear forms invite reading not for neat solutions but for an aesthetic resolution of “shivering fragments,” as she wrote in 1908. While Woolf’s fragmented style is distinctly Modernist, her indeterminacy anticipates a postmodern awareness of the evanescence of boundaries and categories.

Woolf werd als Adeline Virginia Stephen geboren te Londen, in een klassiek Victoriaans gezin. Haar vader Sir Leslie Stephen was een bekend redacteur en literair criticus. Na de dood van haar moeder Julia Jackson in 1895 maakte ze haar eerste zenuwinzinkingdoor. Later zou ze in haar autobiografische verslag "Moments of Being" laten doorschemeren dat zij en haar zuster Vanessa Bellslachtoffer waren geworden van seksueel misbruik door hun halfbroers George en Gerald Duckworth. Na de dood van haar vader verhuisde ze met haar zuster Vanessa naar een huis in Bloomsbury. Ze vormden het begin van een intellectuele kring die bekend zou worden als de Bloomsbury-group, en waarvan onder meer John Maynard Keynes deel zou uitmaken.

In 1905 maakte ze van schrijven haar beroep. Aanvankelijk schreef ze voor het Times Literary Supplement. In 1912 trouwde ze metLeonard Woolf, een ambtenaar en politicoloog. Haar eerste boek, The Voyage Out, kwam uit in 1915. Virginia en haar man woonden afwisselend in Londen en Rodmell, waar ze in 1919 Monk's House hadden aangekocht. Ze publiceerde romans en essays, en had zowel bij de literaire kritiek als het grote publiek succes. Veel van haar werk gaf ze zelf uit via de uitgeverij Hogarth Press.

Op 28 maart 1941 pleegde Woolf zelfmoord door haar zakken te vullen met stenen, en zich te verdrinken in de rivier de Ouse nabij haar huis in Rodmell (Sussex). Voor haar echtgenoot liet ze een zelfmoordbriefje achter waarin ze schreef te voelen dat ze weer gek aan het worden was, dat ze stemmen hoorde, dat ze er niet meer tegen kon, haar man tot last was, en daarom maar deed wat het beste was.

Woolf wordt beschouwd als een van de grootste en meest vernieuwende Engelse schrijvers van de twintigste eeuw. In haar werken experimenteerde ze met de stream of consciousness-techniek; de onderliggende psychologische en emotionele motieven van haar personages; en de diverse mogelijkheden van een verbrokkelde vertelstructuur en chronologie.

In het werk van Woolf en haar collega-schrijvers van de Bloomsburygroep zijn de waarden die worden uitgedrukt in de Principia Ethicavan G.E. Moore herkenbaar. Daarin wordt gesteld dat "personal affections and aesthetic enjoyments include all the greatest, and by far the greatest, goods we can imagine".[1]

In 1998 verscheen de roman The Hours van Michael Cunningham waarin het leven van Woolf en haar roman Mrs. Dalloway een prominente rol spelen. In 2002 werd het boek verfilmd met Nicole Kidman als Virginia Woolf. Zij ontving daarvoor een Oscar voor de Beste vrouwelijke hoofdrol.

Woolfs vroege werken, The Voyage Out (1915) en Night and Day (1919), waren nog traditioneel, maar ze werd steeds vernieuwender en schreef Jacob's Room (1922), Mrs Dalloway (1925), To the Lighthouse (1927) en The Waves (1931). Andere experimentele romans zijnOrlando (1928), The Years (1937), en Between the Acts (1941). Ze was de meester van het kritische essay, en enkele van haar mooiste stukken zijn opgenomen in The Common Reader (1925), The Second Common Reader (1933), The Death of the Moth and Other Essays (1942) en The Moment and Other Essays (1948). A Room of One's Own (1929) en Three Guineas (1938) zijn feministische traktaten. Haar biografie van Roger Fry (1940) is een zorgvuldige studie van een vriend. Sommige van haar korte verhalen uit Monday or Tuesday (1921) verschenen met andere verhalen in A Haunted House (1944).

Fictie

- The Voyage Out (1915)

- Night and Day (1919)

- Jacob's Room (1922)

- Mrs. Dalloway (1925)

- To the Lighthouse (1927)

- The Waves (1931)

- The Years (1937)

- Between the Acts (1941)

- Short Fiction:

- Monday or Tuesday (1921)

- A Haunted House and Other Stories (1943)

'Faction'

- Orlando: A Biography (1928)

- Flush (1933)

Non-fictie

- Ezeltje West. Alle brieven aan Vita Sackville-West. In twee delen verschenen bij Uitgeverij IJzer

- The Common Reader (1925)

- A Room of One's Own (1929)

- The Second Common Reader (1933)

- Three Guineas (1938)

- Roger Fry: A Biography (1940)

- The Death of the Moth and Other Essays (1942)

- The Moment and Other Essays (1948)

- Moments of Being

- Modern Fiction (1919)

Leslie Stephen , vader van Virginia

Vanessa Bell , zus van Virginia

Vanessa Bell and her brother, Thoby Stephen, at Fritham, Hampshire.

Vanessa Bell with her youngest brother, Adrian, (Virginia Woolf's sister)

Gerald Duckworth, Virginia Woolf, Thoby Stephen, Vanessa Stephen, and George Duckworth (back row); Adrian Stephen, Julia Duckworth Stephen, and Leslie Stephen (front row) at Alenhoe, Wimbledon in 1892

Vanessa Bell, Julia Jackson Stephen, Thoby Stephen, Adrian Stephen, and Virginia Woolf in 1894

Adrian, Thoby, Vanessa and Virginia, 1892

1892 - from left to right. Horatio Brown, Julia Duckworth Stephen, George Duckworth, Gerald Duckworth, Vanessa, Thoby, Virginia, Adrian Stephen, the dog Shag

A young Vanessa Bell paints while her sister, Virginia Woolf, and two brothers, Thoby and Adrian, look on

The Stephen children; Adrian, Thoby, Vanessa and Virginia

Thoby, Vanessa, Virginia, Julia, and Adrian Stephen, 1894. Plate 38a Leslie Stephen Photograph Album, Smith College.

(back row) Virginia (Woolf), Vanessa (Bell), Thoby Leslie Stephen ; (front row) Gerald Duckworth, Adrian Stephen Stella Duckworth after the death of her mother Julia (Jackson) Stephen - 1895

Julia Jackson Stephen, Vanessa Bell, Thoby Stephen and Virginia Woolf at Talland House in St. Ives in 1894

Angelica Garnett, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, Virginia Woolf, John Maynard Keynes and Lydia Lopokova sitting outside. Picture from Virginia Woolf Monk's House photograph album,

T. S. Eliot and Virginia Woolf

Henry H. H. Cameron (1852-1911): Julia Stephen with Virginia on her lap 1884

In this house LEONARD and VIRGINIA WOOLF lived 1915-1924 and founded the Hogarth Press 1917

Lytton Strachey and Virginia Woolf.

left to right: Noel Olivier; Maitland Radford; Virginia Woolf (née Stephen); Rupert Brooke

Talland House at St. Ives, Cornwall, England. Holiday home of the Stephen family.

Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell plaing cricket

Virginia Woolf sitting in an armchair at Monk's House.

Signature of Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf with her father, Sir Leslie Stephen (1832-1904)

Virginia Woolf's bed at Monk's House

Virginia Woolf (1882-1941) was an English novelist, essayist, biographer, and feminist. Woolf was a prolific writer, whose modernist style changed with each new novel.[1] Her letters and memoirs reveal glimpses of Woolf at the center of English literary culture during the Bloomsbury era. Woolf represents a historical moment when art was integrated into society, as T.S. Eliotdescribes in his obituary for Virginia. “Without Virginia Woolf at the center of it, it would have remained formless or marginal…With the death of Virginia Woolf, a whole pattern of culture is broken.”[2]

Virginia Adeline Stephen was the third child of Leslie Stephen, a Victorian man of letters, and Julia Duckworth. The Stephen family lived at Hyde Park Gate in Kensington, a respectable English middle class neighborhood. While her brothers Thoby and Adrian were sent to Cambridge, Virginia was educated by private tutors and copiously read from her father’s vast library of literary classics. She later resented theDEGRADATION of women in a patriarchal society, rebuking her own father for automatically sending her brothers to schools and university, while she was never offered a formal education.[3] Woolf’s Victorian upbringing would later influence her decision to participate in the Bloomsbury circle, noted for their original ideas and unorthodox relationships. As biographer Hermione Lee argues “Woolf was a ‘modern’. But she was also a late Victorian. The Victorian family past filled her fiction, shaped her political analyses of society and underlay the behaviour of her social group.”[4]

of women in a patriarchal society, rebuking her own father for automatically sending her brothers to schools and university, while she was never offered a formal education.[3] Woolf’s Victorian upbringing would later influence her decision to participate in the Bloomsbury circle, noted for their original ideas and unorthodox relationships. As biographer Hermione Lee argues “Woolf was a ‘modern’. But she was also a late Victorian. The Victorian family past filled her fiction, shaped her political analyses of society and underlay the behaviour of her social group.”[4]

Mental Illness

In May 1895, Virginia’s mother died from rheumatic fever. Her unexpected and tragic death caused Virginia to have a mental breakdown at age 13. A second severe breakdown followed the death of her father, Leslie Stephen, in 1904. During this time, Virginia first attempted suicide and was institutionalized. According to nephew and biographer Quentin Bell, “All that summer she was mad.”[5] The death of her close brother Thoby Stephen, from typhoid fever in November 1906 had a similar effect on Woolf, to such a degree that he would later be re-imagined as Jacob in her first experimental novel Jacob’s Room and later as Percival in The Waves. These were the first of her many mental collapses that would sporadically occur throughout her life, until her suicide in March 1941.

Though Woolf’s mental illness was periodic and recurrent, as Lee explains, she “was a sane woman who had an illness.”[6] Her “madness” was provoked by life-altering events, notably family deaths, her marriage, or the publication of a novel. According to Lee, Woolf’s symptoms conform to the profile of a manic-depressive illness, or bipolar disorder. Leonard, her dedicated lifelong companion, documented her illness with scrupulousness. He categorized her breakdowns into two distinct stages:

“In the manic stage she was extremely excited; the mind race; she talked volubly and, at the height of the attach, incoherently; she had delusions and heard voices…she was violent with her nurses. In her third attack, which began in 1914, this stage lasted for several months and ended by her falling into a coma for two days. During the depressive stage all her thoughts and emotions were the exact opposite of what they had been in the manic stage. She was in the depths of melancholia and despair; she scarcely spoke; refused to eat; refused to believe that she was ill and insisted that her condition was due to her own guilt; at the height of this stage she tried to commit suicide.”[7]

During her life, Woolf consulted at least twelve doctors, and consequently experienced, from the Victorian era to the shell shock of World War I, the emerging medical trends for treating the insane. Woolf frequently heard the medical jargon used for a “nervous breakdown,” and incorporated the language of medicine, degeneracy, and eugenics into her novel Mrs. Dalloway. With the character Septimus Smith, Woolf combined her doctor’s terminology with her own unstable states of mind. When Woolf prepared to write Mrs. Dalloway, she envisioned the novel as a “study of insanity and suicide; the world seen by the sane and the insane side by side.” When she was editing the manuscript, she changed her depiction of Septimus from what read like a record of her own experience as a “mental patient” into a more abstracted character and narrative. However, she kept the “exasperation,” which she noted, should be the “dominant theme” of Septimus’s encounters with doctors.[8]

Bloomsbury

Virginia began to teach English literature and history at an adult-education college in London, in addition to writing articles and reviews for publications, including The Guardian, The Times Literary Supplement, and The National Review. Woolf continued her journalistic endeavors throughout her life, reviewing contemporary and classical literature in modernist reviews like the Athenaeum, The Dial and The Criterion. It was also during this time that Woolf became close friends with young men who shared and stimulated her intellectual interests. The majority of these friends her brother Thoby met at Trinity College, Cambridge in 1899, including Lytton Strachey, Leonard Woolf, and Clive Bell. This group started meeting for ‘Thursday Evenings’ at Gordon Square, London in 1906, which was soon followed by Vanessa Bell’s ‘Friday Club,’ to discuss the arts. With the emergence of these two literary and artistic circles, the unofficial ‘Bloomsbury Group’ came into existence.[9]

In 1924, during the heyday of literary modernism, Virginia Woolf tried to account for what was new about “modern” fiction. She wrote that while all fiction tried to express human character, modern fiction had to describe character in a new way because “on or about December, 1910, human character changed.” Her main example of this change in human character was the “character of one’s cook.” Whereas the “Victorian cook lived like a leviathan in the lower depths,” modern cooks were forever coming out of the kitchen to borrow the Daily Herald and ask “advice about a hat.”

Woolf’s choice of December, 1910 as a watershed referred above all to the first Post-Impressionist Exhibition, organized by her friend Roger Fry in collaboration with her brother-in-law Clive Bell. The exhibition ran from November 8, 1910 to January 15, 1911 and introduced the English public to developments in the visual arts that had already been taking place in France for a generation. More broadly, however, Woolf was alluding to social and political changes that overtook England soon after the death of Edward VII in May, 1910, symbolized by the changing patterns of deference and class and gender relations implicit in the transformation of the Victorian cook. Henry James considered that the death of Edward’s mother Victoria meant the end of one age; Edward’s reign was short (1901-1910), but to those who lived through it, it seemed to stand at the border between the old world and the new. This sense of the radical difference between the "modern" world and the "Edwardian" one, or more broadly the world before and after the First World War, became a major theme of Woolf's fiction.

In 1911, the year after human character changed, Virginia decided to live in a house in the Bloomsbury neighborhood near the British Museum with several men, none of whom was her husband. Some of her relatives were shocked, and her father’s old friend Henry James found her lifestyle rather too Bohemian. Her housemates were her brother Adrian,John Maynard Keynes, Duncan Grant, and Leonard Woolf, whom she married a year later. Grant and Keynes were lovers, and the heterosexual members of the group too were known for their unconventional relationships. Virginia’s sister, the painter Vanessa Bell, lived for much of her life with Grant, who was also her artistic collaborator, and the two had a daughter. Throughout all this, Vanessa remained married to Clive Bell, who early in marriage had a flirtatious relationship with Virginia, while Duncan had a series of homosexual love affairs. Most of the men in the Bloomsbury group had gone to Cambridge, and many had belonged to an intellectual club called the Apostles, which, under the influence of the philosopher G. E. Moore, emphasized the importance of friendship and aesthetic experience, a more earnest form of Oscar Wilde’s aestheticism.

A typical Bloomsbury figure, Lytton Strachey, wrote his best-known book, Eminent Victorians (1918), in a satirical vein, debunking the myths surrounding suchREVERED figures as Florence Nightingale. Strachey was the most open homosexual of the group, and Woolf vividly recalled his destruction of all the Victorian proprieties when he noted a stain on Vanessa’s dress and remarked, “Semen”: “With that one word all barriers of reticence and reserve went down."

figures as Florence Nightingale. Strachey was the most open homosexual of the group, and Woolf vividly recalled his destruction of all the Victorian proprieties when he noted a stain on Vanessa’s dress and remarked, “Semen”: “With that one word all barriers of reticence and reserve went down."

Feminist Critiques

Woolf wrote extensively on the problem of women’s access to the learned professions, such as academia, the church, the law, and medicine, a problem that was exacerbated by women’s exclusion from Oxford and Cambridge. Woolf herself never went to university, and she resented the fact that her brothers and male friends had had an opportunity that was denied to her. Even in the realm of literature, Woolf found, women in literary families like her own wereEXPECTED to write memoirs of their fathers or to edit their correspondence. Woolf did in fact write a memoir of her father, Leslie Stephen, after his death, but she later wrote that if he had not died when she was relatively young (22), she never would have become a writer.

to write memoirs of their fathers or to edit their correspondence. Woolf did in fact write a memoir of her father, Leslie Stephen, after his death, but she later wrote that if he had not died when she was relatively young (22), she never would have become a writer.

Woolf also concerned herself with the question of women’s equality with men in marriage, and she brilliantly evoked the inequality of her parents’ marriage in her novel To the Lighthouse (1927). Woolf based the Mr. and Mrs. Ramsay on her parents. Vanessa Bell immediately decoded the novel, discovering that Mrs. Ramsay was based on their mother, Julia Duckworth Stephen. Vanessa felt that it was “almost painful to have her so raised from the dead.”[10] Woolf’s mother was always eager to fulfill the Victorian ideal that Woolf later described, in a figure borrowed from a pious Victorian poem, as that of the “Angel in the House.” Woolf spoke of her partly successful attempts to kill off the “Angel in the House,” and to describe the possibilities for emancipated women independently of her mother’s sense of the proprieties.

The disparity Woolf saw in her parents’ marriage made her determined that “the man she married would be as worthy of her as she of him. They were to be equal partners.”[11] Despite numerous marriage proposals throughout her young adulthood, including offers by Lytton Strachey and Sydney Waterlow, Virginia only hesitated with Leonard Woolf, a cadet in the Ceylon Civil Service. Virginia wavered, partly due to her fear of marriage and the emotional and sexual involvement the partnership requires. She wrote to Leonard: “As I told you brutally the other day, I feel no physical attraction in you. There are moments—when you kissed me the other day was one—when I feel no more than a rock. And yet your caring for me as you do almost overwhelms me. It is so real, and so strange.”[12] Virginia eventually accepted him, and at age 30, she married Leonard Woolf in August 1912. For two or three years, they shared a bed, and for several more a bedroom. However, with Virginia’s unstable mental condition, they followed medical advice and did not have children.

Related to the unequal status of marriage was the sexual double standard that treated lack of chastity in a woman as a serious social offense. Woolf herself was almost certainly the victim of some kind of sexual abuse at the hands of one of her half-brothers, as narrated in her memoir Moments of Being. More broadly, she was highly conscious of the ways that men had access to and knowledge of sex, whereas women of the middle and upper classes wereEXPECTED to remain ignorant of it. She often puzzled about the possibility of a literature that would treat sexuality and especially the sexual life of women frankly, but her own works discuss sex rather indirectly.

to remain ignorant of it. She often puzzled about the possibility of a literature that would treat sexuality and especially the sexual life of women frankly, but her own works discuss sex rather indirectly.

If much of Woolf’s feminist writing concerns the problem of equality of access to goods that have traditionally been monopolized by men, her literary criticism prefigures two other concerns of later feminism: the reclaiming of a female tradition of writing and the deconstruction of gender difference. In A Room of One’s Own (1929), Woolf imagines the fate of Shakespeare’s equally brilliant sister Judith (in fact, his sister’s name was Joan). Unable to gain access to the all-male stage of Elizabethan England, or to obtain any formal education, Judith would have been forced to marry and abandon her literary gifts or, if she had chosen to run away from home, would have been driven to prostitution. Woolf traces the rise of women writers, emphasizing in particular Jane Austen, the Brontës, and George Eliot, but alluding too to Sappho, one of the first lyric poets. Faced with the question of whether women’s writing is specifically feminine, she concludes that the great female authors “wrote as women write, not as men write.” She thus raises the possibility of a specifically feminine style, but at the same time she emphasizes (citing the authority of Coleridge) that the greatest writers, among whom she includes Shakespeare, Jane Austen, and Marcel Proust, are androgynous, able to see the world equally from a man’s and a woman’s perspective.

The Effect of War

The theme of how to make sense of the changes wrought in English society by the war, specifically from the perspective of a woman who had not seen battle, became central to Woolf's work. In her short story “Mrs. Dalloway in Bond Street” (1922), Woolf has her society hostess, Clarissa Dalloway, observe that since the war, “there are moments when it seems utterly futile…—simply one doesn’t believe, thought Clarissa, any more in God.” Although her first novel, The Voyage Out (1915) had tentatively embraced modernist techniques, her second, Night and Day (1919), returned to many Victorian conventions. The young modernist writer Katherine Mansfield thought that Night and Day contained “a lie in the soul” because it failed to refer to the war or recognize what it had meant for fiction. Mansfield, who had written a number of important early modernist stories, died at the age of 34 in 1923, and Woolf, who had published some of her work at the Hogarth Press, often measured herself against this friend and rival. Mansfield’s criticism of Night and Day as “Jane Austen up-to-date” stung Woolf, who, in three of her major modernist novels of the 1920s, grappled with the problem of how to represent the gap in historical experience presented by the war. The war is a central theme in her three major modernist novels of the 1920s: Jacob's Room (1922), Mrs. Dalloway (1925), and To the Lighthouse(1927). Over the course of the decade, these novels trace the experience of incorporating the massive and incomprehensible experience of the war into a vision of recent history.

Hogarth Press

In 1915, Leonard and Virginia moved to Hogarth House, Richmond, and two years later, brought a printing press in order to establish a small, independent publishing house. Though the physical machining required by letterpress exhausted the Woolfs, the Hogarth Press flourished throughout their careers. Hogarth chiefly printed Bloomsbury authors who had little chance of being accepted at established publishing companies. The Woolfs were dedicated to publishing the most experimental prose and poetry and the emerging philosophical, political, and scientific ideas of the day. They published T.S. Eliot, E.M. Forster, Roger Fry, Katherine Mansfield, Clive Bell, Vita Sackville-West, and John Middleton Murry, among numerous others. Though they rejected publishing James Joyce’s Ulysses, they printed T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land and the first English translations of Sigmund Freud. Hogarth additionally published all of Woolf’s novels, providing her the editorial freedom to do as she wished as a woman writer, free from the criticism of a male editor. J.H. Willis explains that Woolf “could experiment boldly, remaking the form and herself each time she shaped a new fiction, responsible only to herself as writer-editor-publisher…She was, [Woolf] added triumphantly, ‘the only woman in England free to write what I like.’ The press, beyond doubt, had given Virginia a room of her own.”[13]

Female Relations

Woolf’s liberated writing parallels her relationships with women, who gave her warm companionship and literary stimulus. In her girlhood, there was Violet Dickinson; in her thirties, Katherine Mansfield; and in her fifties, there was Ethel Smyth. But none of these women emotionally aroused Virginia as did Vita Sackville-West. They met in 1922, and it developed into the deepest relationship that Virginia would ever have outside her family.[14] Virginia and Vita were more different than alike; but their differences in social class, sexual orientation, and politics, were all were part of the attraction. Vita was an outsider to Bloomsbury and disapproved of their literary gatherings. Though the two had different intellectual backgrounds, Virginia found Vita irresistible with her glamorous and aristocratic demeanor. Virginia felt that Vita was “a real woman. Then there is some voluptuousness about her; the grapes are ripe; & not reflective. No. In brain & insight she is not as highly organised as I am. But then she is aware of this, & so lavishes on me the maternal protection which, for some reason, is what I have always wished from everyone.”[15] Though Vita and Virginia shared intimate relations, they both avoided categorizing their relationship as lesbian. Vita rejected the lesbian political identity and even Woolf’s feminism. Instead, Vita was well-known in her social circles as a “Sapphist.” Virginia, on the other hand, did not define herself as a Sapphist. She avoided all categories, particular those that categorized her in a group defined by sexual behavior.[16]

Woolf’s relationship with Vita ultimately shaped the fictional biography Orlando, a narrative that spans from 1500 to the contemporary day. It follows the protagonist Orlando who is based on “Vita; only with a change about from one sex to another.”[17] For Virginia, Vita’s physical appearance embodied both the masculine and the feminine, and she wrote to Vita that Orlando is “all about you and the lusts of your flesh and the lure of your mind.” Though Virginia and Vita’s love affair only lasted intermittently for about three years, Woolf wrote Orlando as an “elaborate love-letter, rendering Vita androgynous and immortal, transforming her story into a myth.”[18] Indeed, Woolf’s ideal of the androgynous mind is extended in Orlando to an androgynous body.

When it was published in October 1928, Orlando immediately became a bestseller and the novel’s success made Woolf one of the best-known contemporary writers. In the same month, Woolf gave the two lectures at Cambridge, later published as A Room of One’s Own (1929), and actively participated in the legal battles that censored Radclyffe Hall’s lesbian novel, The Well of Loneliness. Despite this concentrated period of reflection on gender and sexual identities, Woolf would wait until 1938 to publish Three Guineas, a text that expands her feminist critique on the patriarchy and militarism.

Suicide

The Bloomsbury Group gradually dispersed, beginning with the death of Lytton Strachey in 1932 and the suicide of his long-time partner Dora Carrington shortly thereafter. Virginia felt the loss of Lytton acutely in her life and her writing; years later she still thought as she wrote, ‘Oh but he won’t read this!” Roger Fry’s death in 1934 also affected Woolf, to such a degree that she would later write his biography (1940). As her friends died, she felt her own life begin to crumble. In January 1941, Woolf became severely depressed, partly due to the strain of completing her novelBetween the Acts. She distrusted her publisher’s praise of the novel; she felt it was “too slight and sketchy.” She instead wanted to delay publication, deciding that it required extensive revision. Yet during this time, Woolf began feeling that she had lost her art; she felt if she could no longer write, she could no longer fully exist. It was “a conviction that her whole purpose in life had gone. What was the point in living if she was never again to understand the shape of the world around or, or be able to describe it?”[19]

Woolf clearly expressed her reasons for committing suicide in her last letter to her husband Leonard: “I feel certain that I am going mad again: I feel we cant go through another of those terrible times. And I shantRECOVER this time. I begin to hear voices, and cant concentrate.”[20] On March 18, she may have attempted to drown herself. Over a week later on March 28, Virginia wrote the third of her suicide letters, and walked the half-mile to the River Ouse, filled her pockets with stones, and walked into the water.[21]

this time. I begin to hear voices, and cant concentrate.”[20] On March 18, she may have attempted to drown herself. Over a week later on March 28, Virginia wrote the third of her suicide letters, and walked the half-mile to the River Ouse, filled her pockets with stones, and walked into the water.[21]

Virginia's body was found by some children, a short way down-stream, almost a month later on April 18. An inquest was held the next day and the verdict was "Suicide with the balance of her mind disturbed." Her body was cremated on April 21 with only Leonard present, and her ashes were buried under a great elm tree just outside the garden at Monk's House, with the concluding words of The Waves as her epitaph, "Against you I will fling myself, unvanquished and unyielding, O Death!"[22]

The last words Virginia Woolf wrote were “Will you destroy all my papers.”[23] Written in the margin of her second suicide letter to Leonard, it is unclear what “papers” he was supposed to destroy—the typescript of her latest novelBetween the Acts; the first chapter of Anon, a project on the history of English literature; or her prolific diaries and letters. If Woolf wished for all of these papers to be destroyed, Leonard disregarded her instructions. He published her novel, compiled significant diary entries into the volume The Writer’s Diary, and carefully kept all of her manuscripts, diaries, letters, thereby preserving Woolf’s unique voice and personality captured in each line.

MONK'S HOUSE

Leonard and Virginia during their engagement, 1912.

Virginia Woolf, original name in full Adeline Virginia Stephen (born January 25, 1882, London, England—died March 28, 1941, near Rodmell, Sussex), English writer whose novels, through their nonlinear approaches to narrative, exerted a major influence on the genre.

While she is best known for her novels, especially Mrs. Dalloway (1925) and To the Lighthouse (1927), Woolf also wrote pioneering essays on artistic theory, literary history, women’s writing, and the politics of power. A fine stylist, she experimented with several forms of biographical writing, composed painterly short fictions, and sent to her friends and family a lifetime of brilliant letters.

Early life and influences

Born Virginia Stephen, she was the child of ideal Victorian parents. Her father,Leslie Stephen, was an eminent literary figure and the first editor (1882–91) of the Dictionary of National Biography. Her mother, Julia Jackson, possessed great beauty and aREPUTATION for saintly self-sacrifice; she also had prominent social and artistic connections, which included Julia Margaret Cameron, her aunt and one of the greatest portrait photographers of the 19th century. Both Julia Jackson’s first husband, Herbert Duckworth, and Leslie’s first wife, a daughter of the novelist William Makepeace Thackeray, had died unexpectedly, leaving her three children and him one. Julia Jackson Duckworth and Leslie Stephen married in 1878, and four children followed: Vanessa (born 1879), Thoby (born 1880), Virginia (born 1882), and Adrian (born 1883). While these four children banded together against their older half siblings, loyalties shifted among them. Virginia was jealous of Adrian for being their mother’s favourite. At age nine, she was the genius behind a family newspaper, the Hyde Park Gate News, that often teased Vanessa and Adrian. Vanessa mothered the others, especially Virginia, but the dynamic between need (Virginia’s) and aloofness (Vanessa’s) sometimes expressed itself as rivalry between Virginia’s art of writing and Vanessa’s of painting.

for saintly self-sacrifice; she also had prominent social and artistic connections, which included Julia Margaret Cameron, her aunt and one of the greatest portrait photographers of the 19th century. Both Julia Jackson’s first husband, Herbert Duckworth, and Leslie’s first wife, a daughter of the novelist William Makepeace Thackeray, had died unexpectedly, leaving her three children and him one. Julia Jackson Duckworth and Leslie Stephen married in 1878, and four children followed: Vanessa (born 1879), Thoby (born 1880), Virginia (born 1882), and Adrian (born 1883). While these four children banded together against their older half siblings, loyalties shifted among them. Virginia was jealous of Adrian for being their mother’s favourite. At age nine, she was the genius behind a family newspaper, the Hyde Park Gate News, that often teased Vanessa and Adrian. Vanessa mothered the others, especially Virginia, but the dynamic between need (Virginia’s) and aloofness (Vanessa’s) sometimes expressed itself as rivalry between Virginia’s art of writing and Vanessa’s of painting.

While Virginia wasRECOVERING , Vanessa supervised the Stephen children’s move to the bohemianBloomsbury section of London. There the siblings lived independent of their Duckworth half brothers, free to pursue studies, to paint or write, and to entertain. Leonard Woolf dined with them in November 1904, just before sailing to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) to become a colonial administrator. Soon the Stephens hosted weekly gatherings of radical young people, including Clive Bell, Lytton Strachey, andJohn Maynard Keynes, all later to achieve fame as, respectively, an art critic, a biographer, and an economist. Then, after a family excursion to Greece in 1906, Thoby died of typhoid fever. He was 26. Virginia grieved but did not slip into depression. She overcame the loss of Thoby and the “loss” of Vanessa, who became engaged to Bell just after Thoby’s death, through writing. Vanessa’s marriage (and perhaps Thoby’s absence) helped transform conversation at the avant-garde gatherings of what came to be known as the Bloomsbury group into irreverent, sometimes bawdy repartee that inspired Virginia to exercise her wit publicly, even while privately she was writing her poignant “

, Vanessa supervised the Stephen children’s move to the bohemianBloomsbury section of London. There the siblings lived independent of their Duckworth half brothers, free to pursue studies, to paint or write, and to entertain. Leonard Woolf dined with them in November 1904, just before sailing to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) to become a colonial administrator. Soon the Stephens hosted weekly gatherings of radical young people, including Clive Bell, Lytton Strachey, andJohn Maynard Keynes, all later to achieve fame as, respectively, an art critic, a biographer, and an economist. Then, after a family excursion to Greece in 1906, Thoby died of typhoid fever. He was 26. Virginia grieved but did not slip into depression. She overcame the loss of Thoby and the “loss” of Vanessa, who became engaged to Bell just after Thoby’s death, through writing. Vanessa’s marriage (and perhaps Thoby’s absence) helped transform conversation at the avant-garde gatherings of what came to be known as the Bloomsbury group into irreverent, sometimes bawdy repartee that inspired Virginia to exercise her wit publicly, even while privately she was writing her poignant “

Reminiscences”—about her childhood and her lost mother—which was published in 1908. Viewing Italian art that summer, she committed herself to creating in language “some kind of whole made of shivering fragments,” to capturing “the flight of the mind.”

Early fiction

Virginia Stephen determined in 1908 to “re-form” the novel by creating a holistic form embracing aspects of life that were “fugitive” from the Victorian novel. While writing anonymous reviews for theTimes Literary Supplement and other journals, she experimented with such a novel, which she calledMelymbrosia. In November 1910, Roger Fry, a new friend of the Bells, launched the exhibit “Manet and the Post-Impressionists,” which introduced radical European art to the London bourgeoisie. Virginia was at once outraged over the attention that painting garnered and intrigued by the possibility of borrowing from the likes of artists Paul Cézanne and Pablo Picasso. As Clive Bell was unfaithful, Vanessa began an affair with Fry, and Fry began a lifelong debate with Virginia about the visual and verbal arts. In the summer of 1911, Leonard Woolf returned from the East. After he resigned from the colonial service, Leonard and Virginia married in August 1912. She continued to work on her first novel; he wrote the anticolonialist novel The Village in the Jungle (1913) and The Wise Virgins (1914), a Bloomsbury exposé. Then he became a political writer and an advocate for peace and justice.

Between 1910 and 1915, Virginia’s mental health was precarious. Nevertheless, she completely recastMelymbrosia as The Voyage Out in 1913. She based many of her novel’s characters on real-life prototypes: Lytton Strachey, Leslie Stephen, her half brother George Duckworth, Clive and Vanessa Bell, and herself. Rachel Vinrace, the novel’s central character, is a sheltered young woman who, on an excursion to South America, is introduced to freedom and sexuality (though from the novel’s inception she was to die before marrying). Woolf first made Terence, Rachel’s suitor, rather Clive-like; as she revised, Terence became a more sensitive, Leonard-like character. After an excursion up the Amazon, Rachel contracts a terrible illness that plunges her into delirium and then death. As possible causes for this disaster, Woolf’s characters suggest everything from poorly washed vegetables to jungle disease to a malevolent universe, but the book endorses no explanation. That indeterminacy, at odds with the certainties of the Victorian era, is echoed in descriptions that distort perception: while the narrative often describes people, buildings, and natural objects as featureless forms, Rachel, in dreams and then delirium, journeys into surrealistic worlds. Rachel’s voyage into the unknown began Woolf’s voyage beyond the conventions of realism.

Woolf’s manic-depressive worries (that she was a failure as a writer and a woman, that she was despised by Vanessa and unloved by Leonard) provoked a suicide attempt in September 1913. Publication of The Voyage Out was delayed until early 1915; then, that April, she sank into a distressed state in which she was often delirious. Later that year she overcame the “vile imaginations” that had threatened her sanity. She kept the demons of mania and depression mostly at bay for the rest of her life.

In 1917 the Woolfs bought a printing press and founded the Hogarth Press, named for Hogarth House, their home in the London suburbs. The Woolfs themselves (she was the compositor while he worked the press) published their own Two Stories in the summer of 1917. It consisted of Leonard’s Three Jews and Virginia’s The Mark on the Wall, the latter about contemplation itself.

Since 1910, Virginia had kept (sometimes with Vanessa) a country house in Sussex, and in 1916 Vanessa settled into a Sussex farmhouse called Charleston. She had ended her affair with Fry to take up with the painter Duncan Grant, who moved to Charleston with Vanessa and her children, Julian and Quentin Bell; a daughter, Angelica, would be born to Vanessa and Grant at the end of 1918. Charleston soon became an extravagantly decorated, unorthodox retreat for artists and writers, especially Clive Bell, who continued on friendly terms with Vanessa, and Fry, Vanessa’s lifelong devotee.

Virginia had kept a diary, off and on, since 1897. In 1919 she envisioned “the shadow of some kind of form which a diary might attain to,” organized not by a mechanical recording of events but by the interplay between the objective and the subjective. Her diary, as she wrote in 1924, would reveal people as “splinters & mosaics; not, as they used to hold, immaculate, monolithic, consistent wholes.” Such terms later inspired critical distinctions, based on anatomy and culture, between the feminine and the masculine, the feminine being a varied but all-embracing way of experiencing the world and the masculine a monolithic or linear way. Critics using these distinctions have credited Woolf with evolving a distinctly feminine diary form, one that explores, with perception, honesty, and humour, her own ever-changing, mosaic self.

Proving that she could master the traditional form of the novel before breaking it, she plotted her next novel in two romantic triangles, with its protagonist Katharine in both. Night and Day (1919) answers Leonard’s The Wise Virgins, in which he had his Leonard-like protagonist lose the Virginia-like beloved and end up in a conventional marriage. In Night and Day, the Leonard-like Ralph learns to value Katharine for herself, not as some superior being. And Katharine overcomes (as Virginia had) class and familial prejudices to marry the good and intelligent Ralph. This novel focuses on the very sort of details that Woolf had deleted from The Voyage Out: credible dialogue, realistic descriptions of early 20th-century settings, and investigations of issues such as class, politics, and suffrage.

Woolf was writing nearly a review a week for the Times Literary Supplement in 1918. Her essay“

Modern Novels” (1919; revised in 1925 as “

Modern Fiction”) attacked the “materialists” who wrote about superficial rather than spiritual or “luminous” experiences. The Woolfs also printed by hand, with Vanessa Bell’s illustrations, Virginia’s Kew Gardens (1919), a story organized, like a Post-Impressionistic painting, by pattern. With the Hogarth Press’s emergence as a major publishing house, the Woolfs gradually ceased being their own printers.

In 1919 they bought a cottage in Rodmell village called Monk’s House, which looked out over the Sussex Downs and the meadows where the River Ouse wound down to the English Channel. Virginia could walk or bicycle to visit Vanessa, her children, and a changing cast of guests at the bohemian Charleston and then retreat to Monk’s House to write. She envisioned a new book that would apply the theories of “

Modern Novels” and the achievements of her short stories to the novel form. In early 1920 a group of friends, evolved from the early Bloomsbury group, began a “Memoir Club,” which met to read irreverent passages from their autobiographies. Her second presentation was an exposé of Victorian hypocrisy, especially that of George Duckworth, who masked inappropriate, unwanted caresses as affection honouring their mother’s memory.

In 1921 Woolf’s minimally plotted short fictions were gathered in Monday or Tuesday. Meanwhile, typesetting having heightened her sense of visual layout, she began a new novel written in blocks to be surrounded by white spaces. In “

On Re-Reading Novels” (1922), Woolf argued that the novel was not so much a form but an “emotion which you feel.” In Jacob’s Room (1922) she achieved such emotion, transforming personal grief over the death of Thoby Stephen into a “spiritual shape.” Though she takes Jacob from childhood to his early death in war, she leaves out plot, conflict, even character. The emptiness of Jacob’s room and the irrelevance of his belongings convey in their minimalism the profound emptiness of loss. Though Jacob’s Room is an antiwar novel, Woolf feared that she had ventured too far beyond representation. She vowed to “push on,” as she wrote Clive Bell, to graft such experimental techniques onto more-substantial characters.

Major period

At the beginning of 1924, the Woolfs moved their city residence from the suburbs back to Bloomsbury, where they were less isolated from London society. Soon the aristocratic Vita Sackville-West began to court Virginia, a relationship that would blossom into a lesbian affair. Having already written a story about a Mrs. Dalloway, Woolf thought of a foiling device that would pair that highly sensitive woman with a shell-shocked war victim, a Mr. Smith, so that “the sane and the insane” would exist “side by side.” Her aim was to “tunnel” into these two characters until Clarissa Dalloway’s affirmations meet Septimus Smith’s negations. Also in 1924 Woolf gave a talk at Cambridge called “

Character in Fiction,” revised later that year as the Hogarth Press pamphlet Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown. In it she celebrated the breakdown in patriarchal values that had occurred “in or about December, 1910”—during Fry’s exhibit “Manet and the Post-Impressionists”—and she attacked “materialist” novelists for omitting the essence of character.

In Mrs. Dalloway (1925), the boorish doctors presume to understand personality, but its essence evades them. This novel is as patterned as a Post-Impressionist painting but is also so accurately representational that the reader can trace Clarissa’s and Septimus’s movements through the streets of London on a single day in June 1923. At the end of the day, Clarissa gives a grand party and Septimus commits suicide. Their lives come together when the doctor who was treating (or, rather, mistreating) Septimus arrives at Clarissa’s party with news of the death. The main characters are connected by motifs and, finally, by Clarissa’s intuiting why Septimus threw his life away.

In two 1927 essays, “

The Art of Fiction” and “

The New Biography,” she wrote that fiction writers should be less concerned with naive notions of reality and more with language and design. However restricted by fact, she argued, biographers should yoke truth with imagination, “granite-like solidity” with “rainbow-like intangibility.” Their relationship having cooled by 1927, Woolf sought to reclaim Sackville-West through a “biography” that would include Sackville family history. Woolf solved biographical, historical, and personal dilemmas with the story of Orlando, who lives from Elizabethan times through the entire 18th century; he then becomes female, experiences debilitating gender constraints, and lives into the 20th century. Orlando begins writing poetry during the Renaissance, using history and mythology as models, and over the ensuing centuries returns to the poem “

The Oak Tree,” revising it according to shifting poetic conventions. Woolf herself writes in mock-heroic imitation of biographical styles that change over the same period of time. Thus, Orlando: A Biography (1928) exposes the artificiality of both gender and genre prescriptions. However fantastic, Orlando also argues for a novelistic approach to biography.

In 1921 John Maynard Keynes had told Woolf that her memoir “on George,” presented to the Memoir Club that year or a year earlier, represented her best writing. Afterward she was increasingly angered by masculine condescension to female talent. In A Room of One’s Own (1929), Woolf blamed women’s absence from history not on their lack of brains and talent but on their poverty. For her 1931 talk “

Professions for Women,” Woolf studied the history of women’s education and employment and argued that unequal opportunities for women negatively affect all of society. She urged women to destroy the “angel in the house,” a reference to Coventry Patmore’s poem of that title, the quintessential Victorian paean to women who sacrifice themselves to men.

Late work

From her earliest days, Woolf had framed experience in terms of oppositions, even while she longed for a holistic state beyond binary divisions. The “perpetual marriage of granite and rainbow” Woolf described in her essay “

The New Biography” typified her approach during the 1930s to individual works and to a balance between writing works of fact and of imagination. Even before finishing The Waves, she began compiling a scrapbook of clippings illustrating the horrors of war, the threat of fascism, and the oppression of women. The discrimination against women that Woolf had discussed in A Room of One’s Own and “

Professions for Women” inspired her to plan a book that would trace the story of a fictional family named Pargiter and explain the social conditions affecting family members over a period of time. In The Pargiters: A Novel-Essay she would alternate between sections of fiction and of fact. For the fictional historical narrative, she relied upon experiences of friends and family from the Victorian Age to the 1930s. For the essays, she researched that 50-year span of history. The task, however, of moving between fiction and fact was daunting.

Woolf took a holiday from The Pargiters to write a mock biography of Flush, the dog of poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Lytton Strachey having recently died, Woolf muted her spoof of his biographical method; nevertheless, Flush (1933) remains both a biographical satire and a lighthearted exploration of perception, in this case a dog’s. In 1935 Woolf completed Freshwater, an absurdist drama based on the life of her great-aunt Julia Margaret Cameron. Featuring such other eminences as the poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and the painter George Frederick Watts, this riotous play satirizes high-minded Victorian notions of art.

Meanwhile, Woolf feared she would never finish The Pargiters. Alternating between types of prose was proving cumbersome, and the book was becoming too long. She solved this dilemma by jettisoning the essay sections, keeping the family narrative, and renaming her book The Years. She narrated 50 years of family history through the decline of class and patriarchal systems, the rise of feminism, and the threat of another war. Desperate to finish, Woolf lightened the book with poetic echoes of gestures, objects, colours, and sounds and with wholesale deletions, cutting epiphanies for Eleanor Pargiter and explicit references to women’s bodies. The novel illustrates the damage done to women and society over the years by sexual repression, ignorance, and discrimination. Though (or perhaps because) Woolf’s trimming muted the book’s radicalism, The Years (1937) became a best seller.

When Fry died in 1934, Virginia was distressed; Vanessa was devastated. Then in July 1937 Vanessa’s elder son, Julian Bell, was killed in the Spanish Civil War while driving an ambulance for the Republican army. Vanessa was so disconsolate that Virginia put aside her writing for a time to try to comfort her sister. Privately a lament over Julian’s death and publicly a diatribe against war, Three Guineas (1938) proposes answers to the question of how to prevent war. Woolf connected masculine symbols of authority with militarism and misogyny, an argument buttressed by notes from her clippings about aggression, fascism, and war.

Still distressed by the deaths of Roger Fry and Julian Bell, she determined to test her theories about experimental, novelistic biography in a life of Fry. As she acknowledged in “

The Art of Biography” (1939), the recalcitrance of evidence brought her near despair over the possibility of writing an imaginative biography. Against the “grind” of finishing the Fry biography, Woolf wrote a verse play about the history of English literature. Her next novel, Pointz Hall (later retitled Between the Acts), would include the play as a pageant performed by villagers and would convey the gentry’s varied reactions to it. As another holiday from Fry’s biography, Woolf returned to her own childhood with “

A Sketch of the Past,” a memoir about her mixed feelings toward her parents and her past and about memoir writing itself. (Here surfaced for the first time in writing a memory of the teenage Gerald Duckworth, her other half brother, touching her inappropriately when she was a girl of perhaps four or five.) Through last-minute borrowing from the letters between Fry and Vanessa, Woolf finished her biography. Though convinced that Roger Fry (1940) was more granite than rainbow, Virginia congratulated herself on at least giving back to Vanessa “her Roger.”

Woolf’s chief anodyne against Adolf Hitler, World War II, and her own despair was writing. During the bombing of London in 1940 and 1941, she worked on her memoir and Between the Acts. In her novel, war threatens art and humanity itself, and, in the interplay between the pageant—performed on a June day in 1939—and the audience, Woolf raises questions about perception and response. DespiteBetween the Acts’s affirmation of the value of art, Woolf worried that this novel was “too slight” and indeed that all writing was irrelevant when England seemed on the verge of invasion and civilization about to slide over a precipice. Facing such horrors, a depressed Woolf found herself unable to write. The demons of self-doubt that she had kept at bay for so long returned to haunt her. On March 28, 1941, fearing that she now lacked the resilience to battle them, she walked behind Monk’s House and down to the River Ouse, put stones in her pockets, and drowned herself. Between the Acts was published posthumously later that year.

Assessment

Woolf’s many essays about the art of writing and about reading itself today retain their appeal to a range of, in Samuel Johnson’s words, “common” (unspecialized) readers. Woolf’s collection of essaysThe Common Reader (1925) was followed by The Common Reader: Second Series (1932; also published as The Second Common Reader). She continued writing essays on reading and writing, women and history, and class and politics for the rest of her life. Many were collected after her death in volumes edited by Leonard Woolf.

Virginia Woolf wrote far more fiction than Joyce and far more nonfiction than either Joyce or Faulkner. Six volumes of diaries (including her early journals), six volumes of letters, and numerous volumes of collected essays show her deep engagement with major 20th-century issues. Though many of her essays began as reviews, written anonymously to deadlines for money, and many include imaginative settings and whimsical speculations, they are serious inquiries into reading and writing, the novel andthe arts, perception and essence, war and peace, class and politics, privilege and discrimination, and the need to reform society.

Woolf’s haunting language, her prescient insights into wide-ranging historical, political, feminist, and artistic issues, and her revisionist experiments with novelistic form during a remarkably productive career altered the course of Modernist and postmodernist letters.

Virginia Woolf (left) laughing with her nephew, Quentin Bell, and Lydia Lopokovna

Virginia Woolf and George Rylands

Adrian Stephen and Virginia Woolf at Talland House in 1886

Julia Jackson Stephen in 1889

Julia Jackson in 1856

Leslie Stephen and Julia Jackson in Switzerland circa 1889

Vanessa Bell, Stella Duckworth and Virginia Woolf in 1896

Virginia Woolf in 1895

Virginia Woolf in 1895

Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West in 1933

Virginia Woolf and Clive Bell at Studland Beach in Dorset in 1909

Virginia Woolf and Clive Bell in 1910

When Virginia Woolf committed suicide on March 28th in 1941, she left behind two suicide notes for her husband Leonard and one for her sister, Vanessa.

The notes to Leonard were widely published in the press and evenmisquoted. Yet, Vanessa’s note is not as well known. Perhaps Vanessa didn’t share the note with others as Leonard did, or maybe the contents did not pique the interest of the gossip-hungry press as much as the other notes. It’s not clear if it was printed in any publications immediately after Virginia’s death, but Leonard later published it in his autobiography “The Journey Not the Arrival Matters,” which came out in 1970.

The note to Vanessa read:

“Sunday

Dearest, You can’t think how I loved your letter. But I feel I have gone too far this time to come back again. I am certain now that I am going mad again. It is just as it was the first time, I am always hearing voices, and I shan’t get over it now. All I want to say is that Leonard has been so astonishingly good, every day, always; I can’t imagine that anyone could have done more for me than he has. We have been perfectly happy until these last few weeks, when this horror began. Will you assure him of this? I feel he has so much to do that he will go on, better without me, and you will help him. I can hardly think clearly anymore. If I could I would tell you what you and the children have meant to me. I think you know. I have fought against it, but I can’t any longer. Virginia.”

Virginia’s note to Vanessa is interesting because it is more of a plea for Vanessa to help Leonard after Virginia’s death than it is an explanation of why she was going to kill herself. Perhaps Virginia’s main concern when she was writing it was not so much to explain what she thought was obvious, but instead to try and soften the blow of her death for those around her, particularly Leonard who had nursed her through multiple suicide attempts and mental breakdowns throughout their long marriage. It appears that Virginia felt Leonard’s life would be better without her, as she wrote in the note, yet she feared Leonard, and others, might blame him for her death. Although suicide notes are usually a list of reasons why a person has decided to kill themselves, it seems Virginia wrote hers solely to accept the blame for her death and dispel any ideas that it was anyone’s fault but her own.

Standing from left to right: Angus Davidson, Duncan Grant, Julian Bell and Leonard Woolf. Seated left to right: Virginia Woolf, Margaret Duckworth, Clive and Vanessa Bell, in the garden at Charleston, circa 1930

Virginia Woolf’s death in March of 1941 brought an end to her 29-year-long marriage to Leonard Woolf.

After her death was announced in the press, Leonard, who had nursed Virginia through many years of mental breakdowns and suicide attempts, received a flood of condolence letters from friends and fans, yet he was inconsolable.

According to theBOOK “Leonard Woolf: A Biography,” in a state of grief, Leonard scribbled the following on a loose piece of paper:

“Leonard Woolf: A Biography,” in a state of grief, Leonard scribbled the following on a loose piece of paper:

“They said ‘Come to tea and let us comfort you.’ But it’s no good. One must be crucified on one’s own private cross. It is a strange fact that a terrible pain in the heart can be interrupted by a little pain in the fourth toe of the right foot. I know that V. will not come across the garden from the Lodge, and yet I look in that direction for her. I know that she is drowned and yet I listen for her to come in at the door. I know that this is the last page and yet I turn it over. There is no limit to one’s stupidity and selfishness.”

Leonard had Virginia’s body cremated, during which the crematorium played a recording of “Dance of the Blessed Spirits” by Gluck. Afterward, Leonard came home and went for a long walk with his friend Willie, who later wrote an account of their conversation that day:

“He [Leonard] spoke with terrible bitterness of the fools who played the music by Gluck…which promised some happy reunion or survival in a future life. ‘She is dead and utterly destroyed,’ he said, and all his profound disbelief in religion and its consolations were present in those words. It was impossible to comfort him in his loneliness and sense of loss…I referred to her belief which he had mentioned in his letter that she thought she was going mad and would notRECOVERthis time, and I said we must believe that her belief was right. He denied this passionately and said ‘No, she could have recovered as she had done from previous attacks.’”

In Leonard’s autobiography “The Journey Not the Arrival Matters,” Leonard wrote about how he and Virginia had always wanted the cavatina from Beethoven’s B flat quartet, Op. 130, to be played during their cremation because there is a gentle lull in the middle of the song that seems like an opportune moment for “gently propelling the dead in the eternity of oblivion.” Yet, when it came time to make the arrangements for Virginia’s cremation, Leonard was so overwhelmed with grief he couldn’t bring himself to request the song and instead played it that evening when he was home alone.

Leonard buried Virginia’s ashes under one of the two intertwined Elm trees in their backyard, which they had nicknamed “Virginia and Leonard,” and marked the spot with a stone tablet engraved with the last lines from her novelThe Waves: “Against you I fling myself, unvanquished and unyielding, O Death! The waves crashed on the shore.”

In the months that followed Virginia’s death, Leonard continued to lead his quiet life at his home in Rodmell, named Monk’s House. His friends advised him not to stay in the house alone but he refused to leave, stating: “It is no good trying to delude oneself that one can escape the consequences of a great catastrophe.” Leonard answered condolence letters, continued to run the Hogarth Press and commissioned a fellow writer to write aBOOK about Virginia, which never came to fruition. Yet, eventually he longed for London, according to his autobiography:

about Virginia, which never came to fruition. Yet, eventually he longed for London, according to his autobiography:

“After Virginia’s death I felt that I must have someplace where I could stay in London in order to be able to do my work there more intensively. So I took a flat in Clifford’s Inn.”

After realizing he disliked the small size of the flat and the close proximity of his neighbors, he decided to move back to his old home in Mecklenburgh Square, which had been damaged by German bombs:

“I could not stand Clifford’s Inn for long, and in April 1942 I got three rooms in my house in Mecklenburgh Square patched up and moved in there. ‘Patched up’ is the right description of the rooms and the house. There were no windows and no ceilings, and nothing in the house, from roof to water pipes, was quite sound. I got my loneliness and my silence (except when the bombs were falling) all right. But I have experienced few things more depressing in my life than to live in a badly bombed flat, withTHE WINDOWSboarded up, during the great war. I stuck it out in Mecklenburgh Square for exactly a year, but by October 1943 I could bear it no longer and took a lease at 24 Victoria Square.”

During this transition phase following Virginia’s death, a curious thing happened. Leonard fell in love. Her name was Trekkie Parsons and she was the sister of one of Leonard’s close friends, Alice Ritchie, who was dying of cancer and had requested a visit from Leonard. During Alice’s long battle with the disease and Leonard’s frequent visits, Leonard became close with Trekkie, who was an artist, and before he knew it, he fell madly in love with her, despite the fact that she was married and more than 20 years his junior.

The two began a curious love affair that would last the rest of Leonard’s life. During their long relationship, Trekkie split her time between Leonard and her husband, who knew all about her affair with Leonard and accepted it. When Leonard was living in Mecklenburgh Square, Trekkie stopped by on Monday nights after her lithography class for a boiled egg, tea and toast. After Leonard moved back to Rodmell, she stayed with him in the home throughout the week and then returned to her husband on the weekend. When Leonard and Trekkie were apart, the two sent each other poetry and love letters and Leonard would whine about not being able to see her enough.

Trekkie was not just a romantic companion for Leonard but also an intellectual one. In a letter he had written to her, he explained that she embodied his belief in “the value of art and and of people and of one’s relations with people. You combine all three values for me and as I said the you which I know to be you is the most beautiful person I’ve known…I love you.”

Although they were a couple, much like his relationship with Virginia, Leonard and Trekkie’s relationship was not sexual. Like Virginia, Trekkie was also wary of sex but also felt it was important to remain loyal to her husband, at least intimately.

Trekkie was very much like a wife to Leonard, cooking most of his meals, redecorating his home in Rodmell, listening to music with him in the sitting-room after dinner (like he had done with Virginia) and going away on holidays and vacations with him.

Leonard continued his writing career after Virginia’s death, publishing the third volume of his series “After the Deluge” in 1953, his five-volume autobiography and “A Calender of Consolation” in 1967. He also served as the editor of the Political Quarterly, served on the Board of Directors for the New Statesman and continued to run his publishing press, Hogarth Press.

Leonard also continued to work in politics, working for the Labour party as the Secretary of the Advisory Committee on International Relations and the Secretary of the Advisory Committee on Imperial Questions and also served as a chairman on the executive committee for the Fabian Society.

In 1960, Leonard revisited Sri Lanka, where he had served as a civil servant in his youth and was surprised by the warm reception he received.